Let’s talk about hackers, not through the eyes of the tech industry but through the eyes of current and former U.S. law enforcement officials. It’s their job to run those people down and throw them in jail.

Let’s talk about hackers, not through the eyes of the tech industry but through the eyes of current and former U.S. law enforcement officials. It’s their job to run those people down and throw them in jail.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation

MK Palmore is an Information Security Risk Management Executive with the FBI’s Cyber Branch in San Francisco. He runs the cyber-security teams assigned to the San Francisco division of the FBI. “My teams here in San Francisco typically play some part in the investigations, where our role is to identify, define attribution, and get those folks into the U.S. Justice system.”

“The FBI is 35,000-plus personnel, U.S.-based, and part of the Federal law enforcement community,” says Palmore. “There are 56 different field offices throughout the United States of America, but we also have an international presence in more than 62 cities throughout the world. A large majority of those cities contain personnel that are assigned there specifically for responsibilities in the cyber-security realm, and often-times are there to establish relationships with our counterparts in those countries, but also to establish relationships with some of the international companies, and folks that are raising their profile as it relates to international cyber-security issues.”

The U.S. Secret Service

It’s not really a secret: In 1865, the Secret Service was created by Congress to primarily suppress counterfeit currency. “Counterfeit currency represented greater than 50% of all the currency in the United States at that time, and that was why the Agency was created,” explained Dr. Ronald Layton, Deputy Assistant Director U.S. Secret Service. “The Secret Service has gone from suppressing counterfeit currency, or economic, or what we used to refer to as paper crimes, to plastic, meaning credit cards. So, we’ve had a progression, from paper, to plastic, to digital crimes, which is where we are today,” he continued.

Protecting Data, Personal and Business

“I found a giant hole in the way that private sector businesses are handling their security,” said Michael Levin. “They forgot one very important thing. They forgot to train their people what to do. I work with organizations to try to educate people — we’re not doing a very good job of protecting ourselves. “

A leading expert in cyber-security, Levin is Former Deputy Director, U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s National Cyber-Security Division. He retired from the government a few years ago, and is now CEO & Founder of the Center for Information Security Awareness.

“When I retired from the government, I discovered something,” he continued. “We’re not protecting our own personal data – so, everybody has a role to play in protecting their personal data, and their family’s data. We’re not protecting our business data. Then, we’re not protecting our country’s data, and there’s nation states, and organized crime groups, and activists, that are coming after us on a daily basis.”

The Modern Hacker: Who They Are, What They Want

There are essentially four groups of cyber-threat activists that we need to be concerned with, explained the FBI’s Palmore. “I break them down as financially-motivated criminal intrusion, threat actors, nation states, hacktivists, and then those security incidents caused by what we call the insider threat. The most prevalent of the four groups, and the most impactful, typically, are those motivated by financial concerns.”

“We’re talking about a global landscape, and the barrier to entry for most financially-motivated cyber-threat actors is extremely low,” Palmore continued. “In terms of looking at who these folks are, and in terms of who’s on the other end of the keyboard, we’re typically talking about mostly male threat actors, sometimes between the ages of, say, 14 and 32 years old. We’ve seen them as young as 14.”

Criminals? Nation states? Hacktivists? Insiders? While that matters to law enforcement, it shouldn’t to individuals and enterprise, said CIFSA’s Levin. “For most people, they don’t care if it’s a nation state. They just want to stop the bleeding. They don’t care if it’s a hacktivist, they just want to get their site back up. They don’t care who it is. They just start trying to fix the problem, because it means their business is being attacked, or they’re having some sort of a failure, or they’re losing data. They’re worried about it. So, from a private sector company’s business, they may not care.”

However, “Law enforcement cares, because they want to try to catch the bad guy. But for the private sector is, the goal is to harden the target,” points out Levin. “Many of these attacks are, you know, no different from a car break-in. A guy breaking into cars is going to try the handle first before he breaks the window, and that’s what we see with a lot of these hackers. Doesn’t matter if they’re nation states, it doesn’t matter if they’re script kiddies. It doesn’t matter to what level of the sophistication. They’re going to look for the open doors first.”

The Secret Service focuses almost exclusively about folks trying to steal money. “Several decades ago, there was a famous United States bank robber named Willie Sutton,” said Layton. “Willie Sutton was asked, why do you rob banks? ‘Because that’s where the money is.’ Those are the people that we deal with.”

Layton explained that the Secret Service has about a 25-year history of investigating electronic crimes. The first electronic crimes taskforce was established in New York City 25 years ago. “What has changed in the last five or 10 years? The groups worked in isolation. What’s different? It’s one thing: They all know each other. They all are collaborative. They all use Russian as a communications modality to talk to one another in an encrypted fashion. That’s what’s different, and that represents a challenge for all of us.”

Work with Law Enforcement

Palmore, Levin, and Layton have excellent, practical advice on how businesses and individuals can protect themselves from cybercrime. They also explain how law enforcement can help. Read more in my article for Upgrade Magazine, “The new hacker — Who are they, what they want, how to defeat them.”

Can you name that Top 40 pop song in 10 seconds? Sure, that sounds easy. Can you name that pop song—even if it’s played slightly out of tune? Uh oh, that’s a lot harder. However, if you can guess 10 in a row, you might share in a cash prize.

Can you name that Top 40 pop song in 10 seconds? Sure, that sounds easy. Can you name that pop song—even if it’s played slightly out of tune? Uh oh, that’s a lot harder. However, if you can guess 10 in a row, you might share in a cash prize. Knowledge is power—and knowledge with the right context at the right moment is the most powerful of all. Emerging technologies will leverage the power of context to help people become more efficient, and one of the first to do so is a new generation of business-oriented digital assistants.

Knowledge is power—and knowledge with the right context at the right moment is the most powerful of all. Emerging technologies will leverage the power of context to help people become more efficient, and one of the first to do so is a new generation of business-oriented digital assistants.

Go ahead, blame the user. You can’t expect end users to protect their Internet of Things devices from hacks or breaches. They can’t. They won’t. Security must be baked in. Security must be totally automatic. And security shouldn’t allow end users to mess anything up, especially if the device has some sort of Web browser.

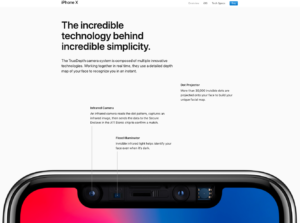

Go ahead, blame the user. You can’t expect end users to protect their Internet of Things devices from hacks or breaches. They can’t. They won’t. Security must be baked in. Security must be totally automatic. And security shouldn’t allow end users to mess anything up, especially if the device has some sort of Web browser. New phones are arriving nearly every day. Samsung unveiled its latest Galaxy S9 flagship. Google is selling lots of its Pixel 2 handset. Apple continues to push its iPhone X. The Vivo Apex concept phone, out of China, has a pop-up selfie camera. And Nokia has reintroduced its famous 8110 model – the slide-down keyboard model featured in the 1999 movie, “The Matrix.”

New phones are arriving nearly every day. Samsung unveiled its latest Galaxy S9 flagship. Google is selling lots of its Pixel 2 handset. Apple continues to push its iPhone X. The Vivo Apex concept phone, out of China, has a pop-up selfie camera. And Nokia has reintroduced its famous 8110 model – the slide-down keyboard model featured in the 1999 movie, “The Matrix.”

Criminals steal money from banks. Nothing new there: As Willie Sutton famously said, “I rob banks because that’s where the money is.”

Criminals steal money from banks. Nothing new there: As Willie Sutton famously said, “I rob banks because that’s where the money is.” I unlock my smartphone with a fingerprint, which is pretty secure. Owners of the new Apple iPhone X unlock theirs with their faces –

I unlock my smartphone with a fingerprint, which is pretty secure. Owners of the new Apple iPhone X unlock theirs with their faces –

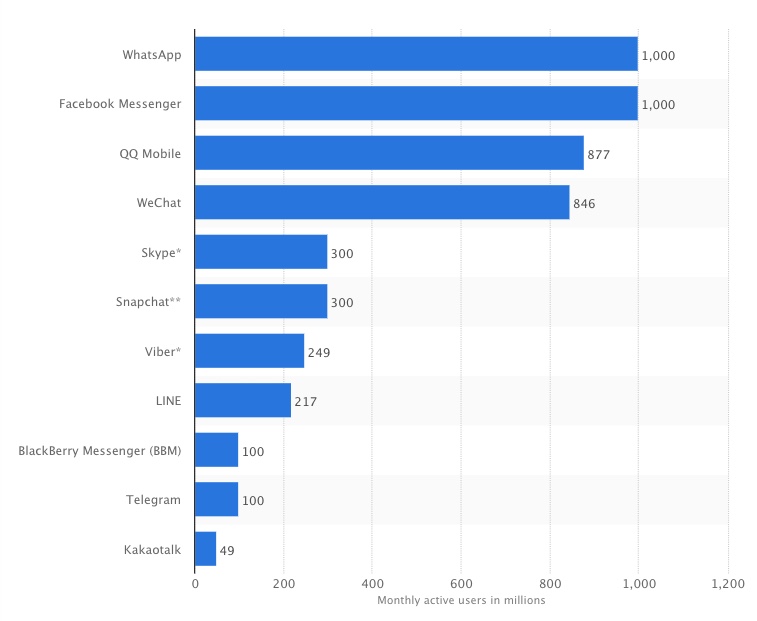

AOL Instant Messenger will be dead before the end of 2017. Yet, instant messages have succeeded far beyond what anyone could have envisioned for either SMS (Short Message Service, carried by the phone company) or AOL, which arguably brought instant messaging to regular computers starting in 1997.

AOL Instant Messenger will be dead before the end of 2017. Yet, instant messages have succeeded far beyond what anyone could have envisioned for either SMS (Short Message Service, carried by the phone company) or AOL, which arguably brought instant messaging to regular computers starting in 1997.

At the current rate of rainfall, when will your local reservoir overflow its banks? If you shoot a rocket at an angle of 60 degrees into a headwind, how far will it fly with 40 pounds of propellant and a 5-pound payload? Assuming a 100-month loan for $75,000 at 5.11 percent, what will the payoff balance be after four years? If a lab culture is doubling every 14 hours, how many viruses will there be in a week?

At the current rate of rainfall, when will your local reservoir overflow its banks? If you shoot a rocket at an angle of 60 degrees into a headwind, how far will it fly with 40 pounds of propellant and a 5-pound payload? Assuming a 100-month loan for $75,000 at 5.11 percent, what will the payoff balance be after four years? If a lab culture is doubling every 14 hours, how many viruses will there be in a week?

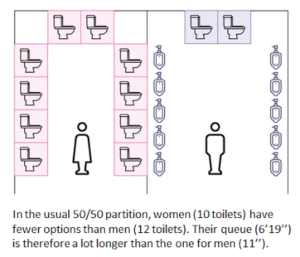

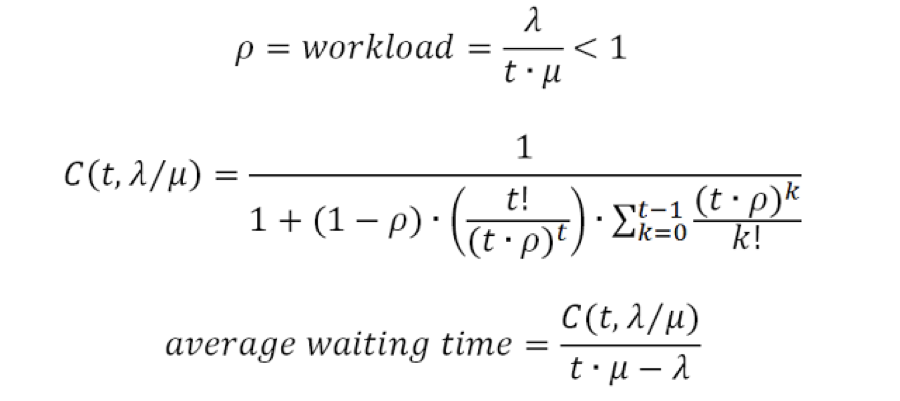

People Queue Magazine has a fascinating new article, “

People Queue Magazine has a fascinating new article, “

Did they tell their customers that data was stolen? No, not right away. When

Did they tell their customers that data was stolen? No, not right away. When  Virtual reality and augmented reality are the darlings of the tech industry. Seemingly every company is interested, even though one of the most interested AR products,

Virtual reality and augmented reality are the darlings of the tech industry. Seemingly every company is interested, even though one of the most interested AR products,  The folks at

The folks at

Twenty years ago, my friend Philippe Kahn introduced the first camera-phone. You may know Philippe as the founder of Borland, and as an entrepreneur who has started many companies, and who has accomplished many things. He’s also a sailor, jazz musician, and, well, a fun guy to hang out with.

Twenty years ago, my friend Philippe Kahn introduced the first camera-phone. You may know Philippe as the founder of Borland, and as an entrepreneur who has started many companies, and who has accomplished many things. He’s also a sailor, jazz musician, and, well, a fun guy to hang out with. Many IT professionals were caught by surprise by last week’s huge cyberattack. Why? They didn’t expect ransomware to spread across their networks on its own.

Many IT professionals were caught by surprise by last week’s huge cyberattack. Why? They didn’t expect ransomware to spread across their networks on its own. To those who run or serve on corporate, local government or non-profit boards:

To those who run or serve on corporate, local government or non-profit boards: “Alexa! Unlock the front door!” No, that won’t work, even if you have an intelligent lock designed to work with the Amazon Echo. That’s because Amazon is smart enough to know that someone could shout those five words into an open window, and gain entry to your house.

“Alexa! Unlock the front door!” No, that won’t work, even if you have an intelligent lock designed to work with the Amazon Echo. That’s because Amazon is smart enough to know that someone could shout those five words into an open window, and gain entry to your house.

It’s official: Internet service providers in the United States can continue to sell information about their customers’ Internet usage to marketers — and to anyone else who wants to use it. In 2016, during the Obama administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) tried to require ISPs to get customer permission before using or sharing information about their web browsing. According to the FCC, the rule change, entitled, “

It’s official: Internet service providers in the United States can continue to sell information about their customers’ Internet usage to marketers — and to anyone else who wants to use it. In 2016, during the Obama administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) tried to require ISPs to get customer permission before using or sharing information about their web browsing. According to the FCC, the rule change, entitled, “ “Call with Alan.” That’s what the calendar event says, with a bridge line as the meeting location. That’s it. For the individual who sent me that invitation, that’s a meaningful description, I guess. For me… worthless! This meeting was apparently sent out (and I agreed to attend) at least three weeks ago. I have no recollection about what this meeting is about. Well, it’ll be an adventure! (Also: If I had to cancel or reschedule, I wouldn’t even know who to contact.)

“Call with Alan.” That’s what the calendar event says, with a bridge line as the meeting location. That’s it. For the individual who sent me that invitation, that’s a meaningful description, I guess. For me… worthless! This meeting was apparently sent out (and I agreed to attend) at least three weeks ago. I have no recollection about what this meeting is about. Well, it’ll be an adventure! (Also: If I had to cancel or reschedule, I wouldn’t even know who to contact.) Wednesday, March 22, spreading from techie to techie. “Better change your iCloud password, and change it fast.” What’s going on?

Wednesday, March 22, spreading from techie to techie. “Better change your iCloud password, and change it fast.” What’s going on?