HTML browser virtualization, not APIs, may be the best way to mobilize existing enterprise applications like SAP ERP, Oracle E-Business Suite or Microsoft Dynamics.

HTML browser virtualization, not APIs, may be the best way to mobilize existing enterprise applications like SAP ERP, Oracle E-Business Suite or Microsoft Dynamics.

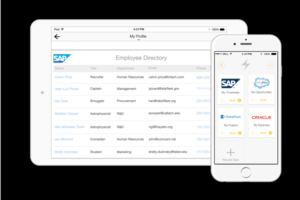

At least, that’s the perspective of Capriza, a company offering a SaaS-based mobility platform that uses a cloud-based secure virtualized browser to screen-scrape data and context from the enterprise application’s Web interface. That data is then sent to a mobile device (like a phone or tablet), where it’s rendered and presented through Capriza’s app.

The process is bidirectional: New transactional data can be entered into the phone’s Capriza app, which transmits it to the cloud-based platform. The Capriza cloud, in turn, opens up a secure virtual browser session with the enterprise software and performs the transaction.

The Capriza platform, which I saw demonstrated last week, is designed for employees to access enterprise applications from their Android or Apple phones, or from tablets.

The platform isn’t cheap – it’s licensed on a per-seat, per-enterprise-application basis, and you can expect a five-digit or six-digit annual cost, at the least. However, Capriza is solving a pesky problem.

Think about the mainstream way to deploy a mobile application that accesses big enterprise back-end platforms. Of course, if the enterprise software vendor offers a mobile app, and if that app meets you needs, that’s the way to go. What if the enterprise software’s vendor doesn’t have a mobile app – or if the software is homegrown? The traditional approach would be to open up some APIs allowing custom mobile apps to access the back-end systems.

That approach is fraught with peril. It takes a long time. It’s expensive. It could destabilize the platform. It’s hard to ensure security, and often it’s a challenge to synchronize API access policies with client/server or browser-based access policies and ACLs. Even if you can license the APIs from an enterprise software vendor, how comfortable are you exposing them over the public Internet — or even through a VPN?

That’s why I like the Capriza approach of using a virtual browser to access the existing Web-based interface. In theory (and probably in practice), the enterprise software doesn’t have to be touched at all. Since the Capriza SaaS platform has each mobile user log into the enterprise software using the user’s existing Web interface credentials, there should be no security policies and ACLs to replicate or synchronize.

In fact, you can think of Capriza as an intentional man-in-the-middle for mobile users, translating mobile transactions to and from Web transactions on the fly, in real time.

As the company explains it, “Capriza helps companies leverage their multi-million dollar investments in existing enterprise software and leapfrog into the modern mobile era. Rather than recreate the wheel trying to make each enterprise application run on a mobile device, Capriza breaks complex, über business processes into mini ones. Its approach bypasses the myriad of tools, SDKs, coding, integration and APIs required in traditional mobile app development approaches, avoiding the perpetual cost and time requirements, risk and questionable ROI.”

It certainly looks like Capriza wins this week’s game of Buzzword Bingo. Despite the marketing jargon, however, the technology is sound, and Capriza has real customers—and has recently landed a US$27 million investment. That means we’re going to see a lot of more this solution.

Can Capriza do it all? Well, no. It works best on plain vanilla Web sites; no Flash, no Java, no embedded apps. While it’s somewhat resilient, changes to an internal Web site can break the screen-scraping technology. And while the design process for new mobile integrations doesn’t require a real programmer, the designer must be very proficient with the enterprise application, and model all the pathways through the software. This can be tricky to design and test.

Plus, of course, you have to be comfortable letting a third-party SaaS platform act as the man-in-the-middle to your business’s most sensitive applications.

Bottom line: If you are mobilizing enterprise software — either commercial or home-grown — that allow browser access, Capriza offers a solution worth considering.

It’s hard being a female programmer or software engineer. Of course, it’s hard for anyone to be a techie, male or female. You have to master a lot of arcane knowledge, and keep up with new developments. You have to be innately curious and inventive. You have to be driven, you have to be patient, and you have to be able to work swiftly and accurately.

It’s hard being a female programmer or software engineer. Of course, it’s hard for anyone to be a techie, male or female. You have to master a lot of arcane knowledge, and keep up with new developments. You have to be innately curious and inventive. You have to be driven, you have to be patient, and you have to be able to work swiftly and accurately. l Sedaka insists that

l Sedaka insists that