It’s a bad idea to intentionally weaken the security that protects hardware, software, and data. Why? Many reasons, including the basic right (in many societies) of individuals to engage in legal activities anonymously. An additional reason: Because knowledge about weakened encryption, back doors and secret keys could be leaked or stolen, leading to unintended consequences and breaches by bad actors.

It’s a bad idea to intentionally weaken the security that protects hardware, software, and data. Why? Many reasons, including the basic right (in many societies) of individuals to engage in legal activities anonymously. An additional reason: Because knowledge about weakened encryption, back doors and secret keys could be leaked or stolen, leading to unintended consequences and breaches by bad actors.

Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, is worried. Some officials in the United States and the United Kingdom want to force technology companies to weaken encryption and/or provide back doors to government investigators.

In comments to the BBC, Sir Tim said that there could be serious consequences to giving keys to unlock coded messages and forcing carriers to help with espionage. The BBC story said:

“Now I know that if you’re trying to catch terrorists it’s really tempting to demand to be able to break all that encryption but if you break that encryption then guess what – so could other people and guess what – they may end up getting better at it than you are,” he said.

Sir Tim also criticized moves by legislators on both sides of the Atlantic, which he sees as an assault on the privacy of web users. He attacked the UK’s recent Investigatory Powers Act, which he had criticised when it went through Parliament: “The idea that all ISPs should be required to spy on citizens and hold the data for six months is appalling.”

The Investigatory Powers Act 2016, which became U.K. law last November, gives broad powers to the government to intercept communications. It requires telecommunications providers to cooperate with government requests for assistance with such interception.

Started with Government

Sir Tim’s comments appear to be motivated by his government’s comments. U.K. Home Secretary Amber Rudd said it is “unacceptable” that terrorists were using apps like WhatsApp to conceal their communications, and that there “should be no place for terrorists to hide.

In the United States, there have been many calls for U.S. officials to own back doors into secure hardware, software or data repositories. One that received widespread attention was in 2016, when the FBI tried to compel Apple to unlock the San Bernardino attack’s iPhone. Apple refused, and this sparked a widespread public debate about the powers of the government to go after terrorists or suspected criminals – and whether companies need to break into their own products, or create intentional weaknesses in encryption.

Ultimately, of course, the FBI received their data through the use of third-party tools to break into the iPhone. That didn’t end the question, and indeed, the debate continues to rage. So why not provide a back door? Why not use crippled encryption algorithms that can be easily broken by those who know the flaw? Why not give law-enforcement officials a “master key” to encryption algorithms?

Aside from legal and moral issues, weakening encryption puts everyone at risk. Someone like Edward Snowden, or a spy, might steal information about the weakness, and offer it to criminals, a state-sponsored organization, or the dark web. And now, everyone – not just the FBI, not only MI5 – can break into systems, potentially without even leaving a fingerprint or a log entry.

Stolen Keys

Consider the widely distributed Content Scramble System used to secure commercial movies on DVD discs. In theory, the DVDs were encoded so that they could only be used on authorized devices (like DVD players) that had paid to license the code. The 40-bit code, introduced around 1996, was compromised in 1999. It’s essentially worthless.

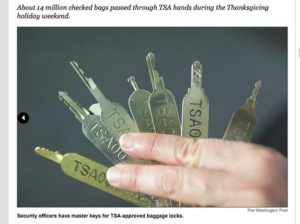

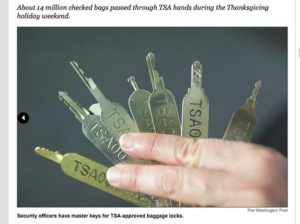

Or consider the “TSA-approved” luggage locks, where the locks were nominally secured by a key or combination. However, there are master keys that allowed airport security staff to open the baggage without cutting off the lock. There were seven master keys, which can open any “TSA-approved” lock – and all seven have been compromised. One famous breach of that system: The Washington Post published a photograph of all the master keys, and based on that photo, hackers could easily reproduce the keys. Whoops!

Speaking of WhatsApp, the software had a flaw in its end-to-end encryption. as was revealed this January. The flaw could let others listen in. The story was first revealed by the Guardian, which wrote

WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption relies on the generation of unique security keys, using the acclaimed Signal protocol, developed by Open Whisper Systems, that are traded and verified between users to guarantee communications are secure and cannot be intercepted by a middleman.

However, WhatsApp has the ability to force the generation of new encryption keys for offline users, unbeknown to the sender and recipient of the messages, and to make the sender re-encrypt messages with new keys and send them again for any messages that have not been marked as delivered.

The recipient is not made aware of this change in encryption, while the sender is only notified if they have opted-in to encryption warnings in settings, and only after the messages have been re-sent. This re-encryption and rebroadcasting of previously undelivered messages effectively allows WhatsApp to intercept and read some users’ messages.

Just Say No

Most (or all) secure systems have their flaws. Yes, they can be broken, but the goal is that if a defect or vulnerability is found, the system will be patched and upgraded. In other words, we expect those secure systems to be indeed secure. Therefore, let’s say “no” to intentional loopholes, back doors, master keys and encryption compromises. We’ve all seen that government secrets don’t stay secret — and even if we believe that government spy agencies should have the right to unlock devices or decrypt communications, none of us want those abilities to fall into the wrong hands.

It has been proven, beyond any doubt whatsoever, that flame decals add 20-25 whp (wheel horsepower) to your vehicle, and of course even more bhp (brake horsepower). I know it’s proven because I read it on the Internet, and everything we read on the Internet is true, not #fakenews. Where did I read it? This incredibly informative blog entry here.

It has been proven, beyond any doubt whatsoever, that flame decals add 20-25 whp (wheel horsepower) to your vehicle, and of course even more bhp (brake horsepower). I know it’s proven because I read it on the Internet, and everything we read on the Internet is true, not #fakenews. Where did I read it? This incredibly informative blog entry here.

IANAL — I am not an attorney. I’ve never studied law, or even been inside a law school. I have a cousin who is an attorney, and quite a few close friends. But IANAL.

IANAL — I am not an attorney. I’ve never studied law, or even been inside a law school. I have a cousin who is an attorney, and quite a few close friends. But IANAL.

Every company should have formal processes for implementing cybersecurity. That includes evaluating systems, describing activities, testing those policies, and authorizing action. After all, in this area, businesses can’t afford to wing it, thinking, “if something happens, we’ll figure out what to do.” In many cases, without the proper technology, a breach may not be discovered for months or years – or ever. At least not until the lawsuits begin.

Every company should have formal processes for implementing cybersecurity. That includes evaluating systems, describing activities, testing those policies, and authorizing action. After all, in this area, businesses can’t afford to wing it, thinking, “if something happens, we’ll figure out what to do.” In many cases, without the proper technology, a breach may not be discovered for months or years – or ever. At least not until the lawsuits begin.

It’s a bad idea to intentionally weaken the security that protects hardware, software, and data. Why? Many reasons, including the basic right (in many societies) of individuals to engage in legal activities anonymously. An additional reason: Because knowledge about weakened encryption, back doors and secret keys could be leaked or stolen, leading to unintended consequences and breaches by bad actors.

It’s a bad idea to intentionally weaken the security that protects hardware, software, and data. Why? Many reasons, including the basic right (in many societies) of individuals to engage in legal activities anonymously. An additional reason: Because knowledge about weakened encryption, back doors and secret keys could be leaked or stolen, leading to unintended consequences and breaches by bad actors.

Judaism is a communal religion. We celebrate together, we mourn together, we worship together, we learn together, and we play together. The sages taught, for example, that you can’t study Torah on your own. We need 10 Jewish adults, a minyan, in order to have a full prayer service. Likewise, while we may observe Shabbat, Hanukkah, and Passover at home, it’s a lot more fulfilling to come together on Friday nights at the sanctuary, at the annual latke fry, or at the community seder.

Judaism is a communal religion. We celebrate together, we mourn together, we worship together, we learn together, and we play together. The sages taught, for example, that you can’t study Torah on your own. We need 10 Jewish adults, a minyan, in order to have a full prayer service. Likewise, while we may observe Shabbat, Hanukkah, and Passover at home, it’s a lot more fulfilling to come together on Friday nights at the sanctuary, at the annual latke fry, or at the community seder. It’s official: Internet service providers in the United States can continue to sell information about their customers’ Internet usage to marketers — and to anyone else who wants to use it. In 2016, during the Obama administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) tried to require ISPs to get customer permission before using or sharing information about their web browsing. According to the FCC, the rule change, entitled, “

It’s official: Internet service providers in the United States can continue to sell information about their customers’ Internet usage to marketers — and to anyone else who wants to use it. In 2016, during the Obama administration, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) tried to require ISPs to get customer permission before using or sharing information about their web browsing. According to the FCC, the rule change, entitled, “

“Call with Alan.” That’s what the calendar event says, with a bridge line as the meeting location. That’s it. For the individual who sent me that invitation, that’s a meaningful description, I guess. For me… worthless! This meeting was apparently sent out (and I agreed to attend) at least three weeks ago. I have no recollection about what this meeting is about. Well, it’ll be an adventure! (Also: If I had to cancel or reschedule, I wouldn’t even know who to contact.)

“Call with Alan.” That’s what the calendar event says, with a bridge line as the meeting location. That’s it. For the individual who sent me that invitation, that’s a meaningful description, I guess. For me… worthless! This meeting was apparently sent out (and I agreed to attend) at least three weeks ago. I have no recollection about what this meeting is about. Well, it’ll be an adventure! (Also: If I had to cancel or reschedule, I wouldn’t even know who to contact.) We received this realistic-looking email today claiming to be from a payment company called FrontStream. If you click the links, it tries to get you to active an account and provide bank details. However… We never requested an account from this company. Therefore, we label it phishing — and an attempt to defraud.

We received this realistic-looking email today claiming to be from a payment company called FrontStream. If you click the links, it tries to get you to active an account and provide bank details. However… We never requested an account from this company. Therefore, we label it phishing — and an attempt to defraud. The U.S. and U.K. are

The U.S. and U.K. are

Was the Russian government behind the 2004 theft of data on about 500 million Yahoo subscribers?

Was the Russian government behind the 2004 theft of data on about 500 million Yahoo subscribers?  As many of you know, I am co-founder and part owner of BZ Media LLC. Yes, I’m the “Z” of BZ Media. Here is exciting news released today about one of our flagship events, InterDrone.

As many of you know, I am co-founder and part owner of BZ Media LLC. Yes, I’m the “Z” of BZ Media. Here is exciting news released today about one of our flagship events, InterDrone. “You walked 713 steps today. Good news is the sky’s the limit!”

“You walked 713 steps today. Good news is the sky’s the limit!”

Nothing you share on the Internet is guaranteed to be private to you and your intended recipient(s). Not on Twitter, not on Facebook, not on Google+, not using Slack or HipChat or WhatsApp, not in closed social-media groups, not via password-protected blogs, not via text message, not via email.

Nothing you share on the Internet is guaranteed to be private to you and your intended recipient(s). Not on Twitter, not on Facebook, not on Google+, not using Slack or HipChat or WhatsApp, not in closed social-media groups, not via password-protected blogs, not via text message, not via email. It was our first-ever perp walk! My wife and I were on the way home from a quick grocery errand, and we were witnesses to and first responders to a nasty car crash. A car ran a red light and hit a turning vehicle head-on.

It was our first-ever perp walk! My wife and I were on the way home from a quick grocery errand, and we were witnesses to and first responders to a nasty car crash. A car ran a red light and hit a turning vehicle head-on.

I was dismayed this morning to find an email from Pebble — the smart watch folks — essentially announcing their demise. The company is no longer a viable concern, says the message, and the assets of the company are being sold to Fitbit. Some of Pebble’s staff will go to Fitbit as well.

I was dismayed this morning to find an email from Pebble — the smart watch folks — essentially announcing their demise. The company is no longer a viable concern, says the message, and the assets of the company are being sold to Fitbit. Some of Pebble’s staff will go to Fitbit as well.

Today’s beautiful cactus flowers will be gone tomorrow.

Today’s beautiful cactus flowers will be gone tomorrow. Mrs. Rachael Adams is back, and still wants to give me a fine Bavarian automobile. But is it a 7-series or a 5-series? Is it a 2015 or 2016 model? Doesn’t matter – it’s a scam. Just like the one a few weeks ago, also from Mrs. Adams, but at least that one was clearer about the vehicle. Hey, it’s the same reg code pin as last time, too. See “

Mrs. Rachael Adams is back, and still wants to give me a fine Bavarian automobile. But is it a 7-series or a 5-series? Is it a 2015 or 2016 model? Doesn’t matter – it’s a scam. Just like the one a few weeks ago, also from Mrs. Adams, but at least that one was clearer about the vehicle. Hey, it’s the same reg code pin as last time, too. See “ Spam scam: Who needs stand-up comedians when laughs appears in my inbox each and every day? This is one of the most amusing in a while, mainly because I can’t parse most of it.

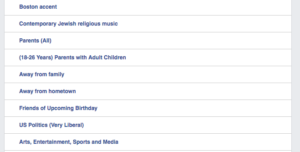

Spam scam: Who needs stand-up comedians when laughs appears in my inbox each and every day? This is one of the most amusing in a while, mainly because I can’t parse most of it. As Aesop wrote in his short fable, “The Donkey and His Purchaser,” you can quite accurately judge people by the company they keep.

As Aesop wrote in his short fable, “The Donkey and His Purchaser,” you can quite accurately judge people by the company they keep. Nothing is scarier than getting together with a buyer (or a seller) to exchange dollars for a product advertised on Craig’s List, eBay or another online service… and then be mugged or robbed. There are certainly plenty of news stories on this subject, but the danger continues. Here are some recent reports:

Nothing is scarier than getting together with a buyer (or a seller) to exchange dollars for a product advertised on Craig’s List, eBay or another online service… and then be mugged or robbed. There are certainly plenty of news stories on this subject, but the danger continues. Here are some recent reports: Can someone steal the data off your old computer? The short answer is yes. A determined criminal can grab the bits, including documents, images, spreadsheets, and even passwords.

Can someone steal the data off your old computer? The short answer is yes. A determined criminal can grab the bits, including documents, images, spreadsheets, and even passwords.